Masters of Storytelling with Data

Dr Lisa McKenzie at LSE (Picture: Elisabeth Blanchet) 12 Mar 2020In this first instalment of our blog series about pioneering women in London, Lucy discusses the importance of both qualitative and quantitative data for compelling storytelling. She draws on the work of two very different master storytellers. Her choices are Florence Nightingale, the legendary lady with the lamp, and Dr Lisa Mckenzie, a fearless working class academic.

In many civil society organisations, collecting and analysing data is the chore that nobody enjoys doing. Yet, data is essential to an organisation’s survival, a fact widely acknowledged by many non-profits we work with. That’s why for this blog, I want to draw on examples of two very inspirational women. Their work illustrates how data can be a powerful tool in the fight for social change and ultimately, in the fight for lives.

The fight for better sanitation

It’s been over a month since COVID-19 erupted into the headlines. We might not have a vaccine yet, but for mapping the movement of the virus, as well as public efforts to contain it, we have Florence Nightingale to thank. The legendary lady with the lamp was, unbeknown to most, the legendary lady with data. It is less well known about Nightingale that she saved millions of lives not with her nursing abilities, but with her penchant for statistics.

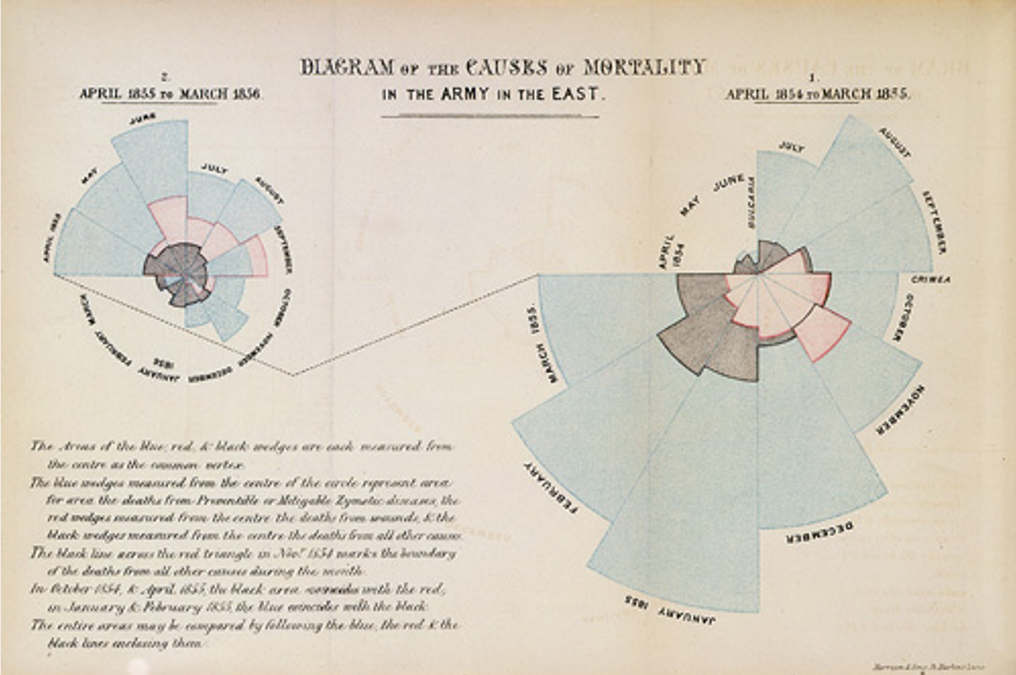

From a young age, Nightingale was a keen statistician. At her childhood home in Mayfair, she measured vegetables and charted their length and weight in cross-tabulations; a hobby which might seem a little drab to you and me. However, her aptitude for measuring led her to log meticulously each soldier’s cause of death when she was working in the Crimea.

As she charted these deaths, she began to notice a pattern emerging from the data. The majority of men were not dying from injuries accrued from combat, but rather from preventable illnesses. They had contracted these due to poor sanitation in the hospitals where they were being treated. Highlighting the importance of poor hygiene to male doctors and surgeons was no easy feat in the 1850s. Nightingale’s critique of on-site sanitation was dismissed due to her gender and “lowly” position as a nurse. But she wasn’t deterred and, following the war, she focused her efforts on weaponizing her data to write a damning report about the impact of poor hygiene on public health.

Data. It’s not just for statisticians

The beauty of Nightingale’s social statistics was how revolutionary they were. Before her efforts, statistical data was presented in long and exceedingly complex formats. But she was a visionary; she knew that reading through these figures was not only a tedious process but also exclusionary. Analysing data required the privileges of an education and a mathematically trained eye. Nightingale wanted to communicate with the general public – and she knew that a picture could tell a thousand words.

Drawing upon her “data hunch”, Nightingale set to work creating a compelling visualisation of this information – one which would not only communicate the importance of hygiene to all, but also one whose message would be irrefutable to the men in positions of power who had ignored her observations.

Her coxcombs and report were a a triumph – and the rest is quite literally history. Following Nightingale’s damning report, hospitals and medical practitioners around the world began to adopt better standards of hygiene and sanitation. An act which in turn has been estimated to have saved millions of lives worldwide. Her efforts demonstrate the importance of storytelling with data. As well as in hospital practices, her contributions live on in the Florence Nightingale museum at St Thomas’ hospital in London.

The fight for the “left out”

Since the 2016 referendum, the debate around the result has seen renewed public interest in the innermost thoughts of otherwise forgotten about communities. But one scholar, who has been conducting ethnography with the so-called “left behind” for many years, took the vote for Brexit as an opportunity to speak up against the relentless bashing of “Leave” constituencies.

Dr Lisa McKenzie is a rebel ethnographer and a working class academic. Like Nightingale, Dr McKenzie is a master storyteller who, early on in her research identified a need to communicate; in particular, a need to both engage and challenge public opinion. Also like Nightingale, Lisa’s broader mission is to use storytelling with data to fight for lives.

In this context, the lives of communities facing bitter austerity, discrimination and the threat of being made homeless by the wave of gentrification engulfing London. Communication and the fight for better data for the purposes of conserving life are, however, the only points of convergence between two otherwise radically different women. Unlike her counterpart who was born into aristocracy, Dr McKenzie grew up in a mining community in Sutton-in-Ashfield.

A proud working class academic

The daughter of a miner and a factory worker, Lisa was raised in a working class household and fought with her family on the pickets during the 1984 Miners Strike. Like most of the women in her community, Lisa left school at 16 to work at Pretty Polly Hosiery. But when she became a mother at 19, she found herself hurled rapidly off course.

Those in positions of power had decided that the “respectable working class” label no longer applied to her case. Dr McKenzie found herself being treated appallingly as a member of the so-called underclass. As a single, young mother of mixed-race child, she experienced first-hand the deeply complex challenges of having an intersectional identity; namely, discrimination on class, gender and race. Discrimination came from not only from her own community, but also from “professionals” working within state infrastructure.

It is this experience of precarity and hardship that makes Lisa such a tour-de-force. Being “out” about one’s class in academia is no easy feat, much like being a lowly nurse criticising hygiene in the mid 1800s. But it is Lisa’s wealth of lived experience, and working class identity, that makes her an asset in this field. And that is why I respect her so much. Dr McKenzie’s gift is her ability to empathise, to truly engage opinions that the academic avant garde find difficult or abhorrent; and it is this aptitude for honesty which makes her a brilliant ethnographer and captivating storyteller.

Social mobility

Dr McKenzie is also no stranger to being shut down by those in power or facing tirades of abuse. Often, she has found herself the centre of a twitter storm for speaking honestly and, on a number of occasions has been arrested for following and engaging in protest. Animosity, however, has never deterred her – and armed with an array of qualitative data, Lisa has fought back for the lives of the “left out” through the medium of academic publications, newspaper articles and countless radio and television interviews.

By telling the stories and showcasing the voices of those communities lambasted by the establishment, Dr McKenzie communicates very effectively her broader finding; that social mobility is a damaging lie, one which is destroying and dismantling the lives of working class communities.

Often, we tend to think of social mobility as something “good” citizens are meant to aspire to. Those of us without privilege should aspire to ascend upward towards a bright future and leave the past behind. But for Lisa, this concept is deeply troubling and, crucially, incorrect. Through years of engagement and immersion in forgotten communities, Lisa’s qualitative data indicates a pattern. By affording opportunity to “the brightest and the best”, we are excluding – by default – whole communities from mainstream society.

Those who are cherry picked, who “done good”, are made by our society to feel ashamed of their origins- to look “downwards” at the communities which raised them, to perceive the latter as class baggage. As such, her research demonstrates (with captivating clarity) that social mobility is a harmful concept because it legitimises exclusion.

“The left behind”

“Brexit has made a difference to working-class people dubbed ‘the left behind’. They have become visible for the first time in generations, and to some extent feared. In January 2018 few could deny that the government’s Brexit plans are chaotic. But for working-class people all over the UK, the chaos of the NHS, Universal Credit, social cleansing and housing is their priority. […] Those who don’t fear the shame of the foodbank, or the looming prospect of a job in the warehouse/workhouse for their children – and instead think the crisis is about the colour of passports – should think themselves lucky.”

Dr Lisa McKenzie (2017, from “The class politics of prejudice: Brexit and the land of no-hope and glory”, British Journal of Sociology:68 (Sup 1)).

London Plus Celebrates pioneering women of civil society

Head to our news page to find out more about this series of blogs and to read about the other women who have made an impact in civil society in London.